Sexual intercourse began in 1963, according to Philip Larkin

‘Sexual intercourse began | In nineteen sixty-three | (Which was rather late for me) – | Between the end of the Chatterley ban | And the Beatles’ first LP.’ Philip Larkin, 1967.

![]()

When the BCS asked people about fear of crime more than a decade after the big retreat began, almost two-thirds thought crime was continually rising, half of whom thought it was going up steeply. Unsurprisingly, readers of tabloids were around twice as likely to worry as readers of broadsheets.

Krista Jansson, British Crime Survey – Measuring crime for 25 years, p. 18 [http://www.usak.org.tr/istanbul/files/bcs25.pdf]

![]()

This misperception is more than just a matter of curiosity; most of us hugely overestimate our own chances of being a victim

A major survey found that on average 14 per cent of people expected to be a victim of violence or burglary in the next twelve months – the actual chances were 2.4 per cent (violence) and 3.2 per cent (burglary). In BCS responses 65 per cent thought crime was rising, and 35 per cent believed it was rising ‘a lot’ – though only 13 per cent judged it was rising a lot where they lived. Source: Chris Kershaw, Sian Nicholas and Alison Walker, Crime in England and Wales 2007/8, Home Office, London, July 2008, ISBN 978-1-84726-753-5

![]()

Yet so deep was the sense of cynicism, hopelessness and anger that it was heresy to tell the truth.

For many years politicians and police chiefs were so trapped in the headlights of public disquiet that one of the government’s foremost responses to crime was a strategy to cut the fear of it. A Home Office working party chaired by Michael Grade reported in 1989, highlighting irrational fears even though crime was then continuing to surge. A toolkit was created to help local councils drive down fear of crime and an initiative was launched to improve the image of criminal justice. Few official reports noted that anxieties about crime often mingled with exasperation and anger.

![]()

The homicide rates in thirteenth-century England were about twice as high as those in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and those of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were some five to ten times higher than those today.

Lawrence Stone, Interpersonal Violence in English Society 1300–1980, Past and Present, No. 101. (November 1983), pp. 22–33, p. 25 [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-2746%28198311%290%3A101%3C22%3AIVIES1%3E2.0.CO%3B2-J]

![]()

As the Kent researcher observed: ‘Every era from the fifteenth century to our own day has produced witnesses eager to testify to the unprecedented violence and criminality of their own generation.’

James S. Cockburn, Patterns of Violence in English Society: Homicide in Kent 1560–1985, Past and Present, No. 130, February 1991, OUP, pp. 70–106, p. 105 [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-2746%28199102%290%3A130%3C70%3APOVIES%3E2.0.CO%3B2-5]

![]()

Known offences in England and Wales rose almost seventy-fold, from 80,000 in 1900 to a peak of 5.5 million in 1995.1 The most reliably recorded crime, murder, went up too, roughly tripling in four decades after 1960.2

1Actually crime appeared to peak again in 2004, but only because the counting rules were changed.

2 The murder figures are especially disconcerting since the increase was largely the sort of killings that most create public anxiety. In the ten years from the mid-1990s, family or acquaintance killings stayed fairly constant at about 400 a year in the UK, but stranger murders rose by a third, albeit from a low base of 99 but climbing to 130, with almost all the increase focused on young males from poorer sections of society. (Figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act: The Times p. 1, pp. 6–7, and editorial, p. 14, 27 December 2006.)

![]()

In the 1960s a prominent psychiatrist who treated young offenders assured us that ‘throughout the last half of the nineteenth century the proportion of the population incarcerated in English prisons was considerably higher than it is now’.1 In fact recorded crime rates in the late nineteenth century were relatively tiny, while the prison population was proportionally about the same.2

1 Donald West, The Young Offender, Penguin, London, 1967, p. 34.

2 In the 1890s about 20,000 were in prison at any one time out of a UK population of under 30 million, a ratio of roughly 1:1,500. In the 1960s the UK prison population was roughly 35,000 when the population was 53 million, again a ratio of about 1:1,500. See Gavin Berman, Prison population statistics, House of Commons Library 24 May 2012, SN/SG/4334, p. 2 for 1960s prison figures for England and Wales [www.parliament.uk%2Fbriefing-papers%2Fsn04334.pdf&ei=2wJYUf3ZBYmYPY2CgcgF&usg=AFQjCNFc5woMqfEk6pJKE2rqLrXlLM5oYg&bvm=bv.44442042,d.ZWU] and for Scotland see Statistical Bulletin, Crime and Justice Series, 29 June 2012, The Scottish Government, p. 1.

![]()

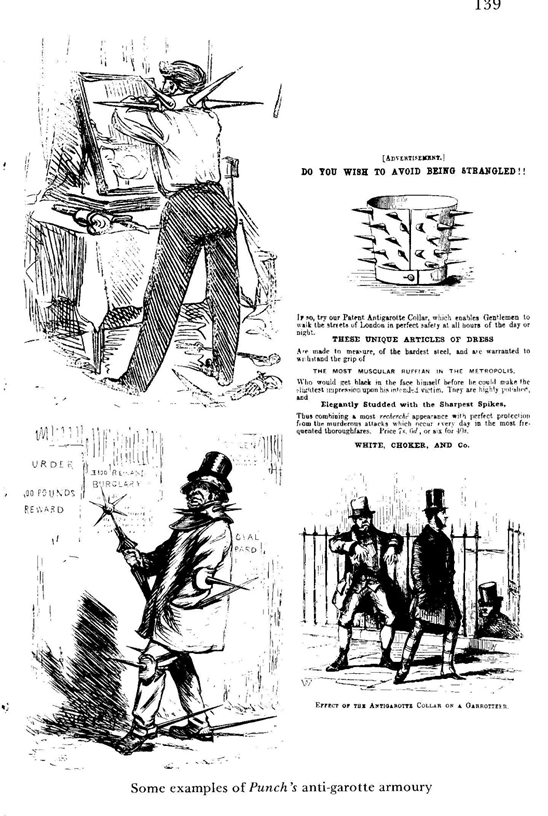

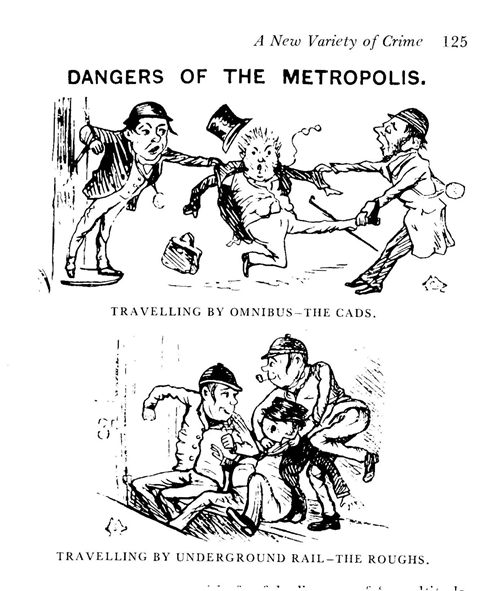

In the 1980s, sociologist Geoffrey Pearson almost went so far as to blame the middle classes for hysteria. His book, Hooligan, A History of Respectable Fears, is still sometimes quoted today as proof that crime is nothing new

Geoffrey Pearson, Hooligan, A History of Respectable Fears, Palgrave Macmillan, 1983, was voted one of seven ‘iconic’ studies in British criminology. It is worth seeing if only for illustrations drawn from Punch which, though satirical, were interpreted by some social scientists in the 1980s as though they were representative of crime at the time.

![]()

![]()

If crime sells papers even when offending rates are relatively low, one could hardly be surprised that it made headlines when crime soared. This was a genuinely worrying phenomenon. Especially to anyone who has worked with victims.

Some victims do find solace that crime is reducing. But for some communities, and many families, crime is a raw, cruel routine blight. In that sense global comparisons, national patterns and long-term trends don’t matter a jot. In 2008, after a British media panic about gun crime had morphed into a scare about knife crime, Britain’s then top-selling tabloid, the News of the World, asked me to chair public meetings called ‘Save Our Streets’. They were electrifying. For many members of the audience, I and the top table with London’s police chief, the government’s crime adviser and the opposition spokesman must have represented a different, ordered, well-heeled world, unlike theirs where privation, fear and violence were part of life. There were parents struggling with bereavement, youth workers thwarted through lack of funds, local politicians calling stridently for tough deterrents, youngsters candid that they had carried knives more out of fear than aggression, and victims pouring scorn on the way they had been treated by the criminal justice system. For them, I suspect, being lectured on how statistics show things are getting better would not be well received.

![]()

Almost all the downward trends were masked at first by figures recorded by police, but as we have seen, property crime began to tumble around 1995 and violent crime subsided five years later. In fact hospital attendance for wounding fell every year from 2001 onwards.2

Vaseekaren Sivarajasingam, J. P. Wells, Simon Moore, P. Morgan, Jon Shepherd, ‘Violence in England and Wales in 2011; An Accident and Emergency Perspective’, Violence and Society Research Group, Cardiff University, 2011. [www.vrg.cf.ac.uk/nvit/NVIT_2011.pdf]

![]()

People consistently think communities elsewhere suffer more crime than they do. And since almost everyone feels the same, we can only be voicing what we have read about or seen on the TV.

Perhaps it is not just the news media but the entertainment industry that stokes our fears. It is certainly not scrupulous about truth or context – as Sam Goldwyn put it, ‘A good movie is one which begins with an earthquake or a volcano eruption and then works up quickly to some kind of climax.’ Video games seem to have taken over from films and TV as the major polluting culprits for crime. For example, after 17 young people were convicted in the wake of a schoolboy’s murder at Victoria Station in London, the detective who led the inquiry said that that the “blitz attack” was fuelled by violent play: ‘You’ve got people playing computer games where they’re shooting and stabbing people. Where is the real world for them?’ (Detective Chief Inspector John McFarlane quoted after the last of a series of Old Baily trials, 25 April 2013). He may be right but he cited no evidence. For sure some people are gullible and many more are suggestible; but most people draw a big distinction between what is presented to them as entertainment and what is claimed to be factual.

![]()

People are often unaware of local crime risks. Those most vulnerable, notably young males, feel more secure than those at slight risk, like the elderly.

According to Dame Helen Reeves, who was chief executive of Victim Support from 1980 to 2005, when the media came to her, as they frequently did, they usually needed a story about violence, ‘ideally featuring a photo of an old lady – and they wanted injuries’. One newspaper offered a publicity deal for Victim Support in return, but when given data showing that woundings to the elderly were uncommon and told that a photo would cause disproportionate fear, the reporter retorted, ‘That’s not what my readers want to read.’ (Conversation with the author.)

![]()

‘A NATION STALKED BY FEAR: Rape up 27 per cent, Violent crime up 22 per cent, Drug offences up 16 per cent.’

This quote, from The Sun in June 2003, was chosen at random from a selection of cuttings. But The Sun is by no means the worst offender. For the UK’s national media an almost-full glass is always partly empty. The Daily Mail especially delights in curmudgeonly news agenda, invariably interpreting good crime news as bad in an inverse version of the way theatres selectively quote critics to transform unfavourable reviews into eulogies. Think Victor Meldrew (an enthusiastically pessimistic pensioner in an old British TV comedy, One Foot in the Grave) and you get the picture.

![]()

In 2009, on the day new figures emerged showing homicide dropping to its lowest level in twenty years, The Times ran: ‘Recession blamed for rise in property crime.’

According to The Sun it was: ‘CRIMECRUNCH UK: shoplifting and bag snatches rocket; Burglaries rise … first time in 6 yrs; Child cruelty is soaring in recession.’

The Daily Mail’s story was: ‘RISE OF THE ONLINE CREDIT CARD SHARPS: Annual crime figures reveal fraud soaring to £610m … Serious knife crime attacks rocket by 50 per cent.’

Only The Guardian was different: ‘Murder rate lowest in 20 years as crime figures show little knock-on effect from recession.’

All headlines taken from the final editions, 17 July 2009.

Even six years later the British media plodded on with their alarmist approach, with the broadsheets still as panicky as their downmarket tabloid cousins. On the day that crime figures plunged to the lowest level since victim surveys began, The Times headline was, “Rapes increase by 30% to hit record high”. You had to read down to paragraph 8 to discover that the rape figures were believed to reflect higher levels of reporting and recording. (The Times, 23 January 2015.)

![]()

‘The researchers, Gavin Hales, Chris Lewis and Daniel Silverstone, said that increasingly firearms had become a normal part of the systematic violence found in the street-level criminal economy.’

The Guardian, London, 15 December 2006. (The newspaper did subsequently carry a correction about confusing Plymouth for Portsmouth.)

![]()

‘Illegal guns are not easy to obtain for most people. The study dispels the urban myth of walking into a pub and buying an illegal gun for £50. The illegal guns are generally only available to a small minority of well-connected criminals and these weapons are often shared around. Even in the communities most seriously affected by gun crime, the vast majority of people have nothing to do with guns or crime.’

Press notice No. 166 issued by the University of Portsmouth, 14 December 2006. The original research paper is Home Office Research Study 298, Gun crime: the market in and use of illegal firearms, Gavin Hales, Chris Lewis and Daniel Silverstone, London, December 2006.[http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs06/hors298.pdf]

![]()

Journalism is about narrative and narrative is about marshalling the facts to fit the story. It is very natural to want to elbow any context if it doesn’t help the theme. And I can tell you from long personal experience that journalists are under intense pressures to ‘stand a story up’.

The skill is in uncovering the bits that fit the editor’s preconceptions, but never ‘over-researching’ to the point where you find the story isn’t true. As journalists say, only half-jokingly: ‘Don’t let the facts spoil a good story.’ If you go back and say things aren’t what they seemed, next time your editor may find a reporter who can make the story stand up. Indeed, in my early days as a reporter on The World at One those very words were used to me by a frustrated producer. These pressures are especially intense on running stories and on daily papers, and they are not confined to tabloids. Once you have the story you must write it in the most engaging way, which is usually to emphasise the starkest aspect at the expense of others which complicate or detract from it. Finally, however carefully crafted your own account might be, it goes to a sub-editor who makes it more dramatic and writes an attention-grabbing heading that may, or may not, reflect the tone of your report.

![]()

As someone once remarked, ‘scrutinising the British press for sinister motives in its coverage of crime may be a waste of subtlety’.

Colin Wilson, The Times, London 28 January 2006, p. 25.

![]()

… homicides involving firearms had almost halved in the previous five years, from a peak of ninety-five to fifty. This inconvenient truth was comprehensively ignored, not least by the public-service BBC.

I even failed to persuade Crimewatch colleagues to set gun crime in context when we reconstructed one of a spate of shootings in early 2007 (Crimewatch, BBC One, 5 March 2007). Producers felt that adding a line about declining firearms homicide would detract from the appeal. They may have been right, and this is frequently why journalists drop anything which spoils a simple narrative, but reporting clusters of gun crimes with a simple narrative was likely to bolster the impression that it was then a widespread and growing problem.

![]()

It was left to the website Spiked to point out that: ‘In America there is an average gun-killing rate of 3.97 per 100,000 of the population; in Canada it is 0.59; in Switzerland it is 0.51; in Sweden it is 0.37; in England and Wales it is 0.14.’ In fact, because UK gun laws are drawn so widely, half of all firearms offences in England and Wales were kids playing with airguns and paintballs (10,437 out of 21,521 recorded gun crimes, seven of which had caused serious injury in 2006), and another third involved imitations such as toy guns, pellet guns or just sticks concealed under a coat. Even the presumed real weapons were rarely discharged.

Brendan O’Neill, Spiked, 20 February 2007 [www.spiked-online.com/index.php?/site/article/2877/]

![]()

Incidentally, given that murder attracts more publicity than most crimes, you might be surprised to know that by far the most common victims of homicide in Britain are babies.1 Infants suffer one-and-a-half times as many killings as the next most vulnerable group, young adults.2

1 ‘By far the highest homicide rates in both sexes are in infants, with 44 homicides per million per annum in males and 35 per million in females. Once past infancy, rates fall rapidly so that they are lowest in both sexes between the ages of 5 and 14. They rise again in young adults, with a plateau around 12–15 per million in women from age 20 to 49, falling to around 5 per million in middle age then rising in those over 80 to around 12 per million. Men show a second peak around 33 per million in their twenties which gradually falls to a low of 10 per million around 70 years of age, then rises again to 14 in those aged 85 and over.’ Tim Devis and Cleo Rooney, Recent trends in deaths from homicide in England and Wales, Health Statistics Quarterly, 1999, No. 3, pp. 5–13. ISSN 1465-1645.

2 In 2011/12, infants under the age of one suffered twenty-one homicides per million population compared with a rate at fifteen per million for those aged sixteen to twenty-nine. Crime Survey for England & Wales, Statistical Bulletin, Office of National Statistics, Home Office, 2013.

![]()

In 2008 the headlines were dominated by knives, almost to the exclusion of any other category of violent offence. Yet at that time the BCS showed knife crime was stable. Police figures in London – where the problem was said to be worst – recorded a 15 per cent year-on-year drop.

This is not to downplay the fact that knife crime was a major problem at the time in a few urban areas of Britain, especially among some ethnic minorities, though the Metropolitan Police recorded a fall from 12,122 offences in 2006/7 to 10,220 in 2007/8. A study at King’s College London confirmed that while murders of the middle-aged were becoming less frequent, teenagers were being murdered slightly more often, an annual toll of around two dozen which had only intermittently been given attention before.

![]()

In crime coverage, as in reporting other stories, there is a natural tendency to reflect back to us the images we want to watch and read and buy.

Thus more educated people tend to disparage tabloid journalism while accepting the juicy but often none too scrupulous agenda set by it. Increasingly competition extends to broadcasting too, often serving to reinforce our views rather than confound them. If our world view is confounded on radio or TV we are likely to switch channel. Inevitably the media play to the crowd, selecting staff, stories and interpretations that work best in their market.

![]()

The American media commentator Michael Wolff expressed it with typical flourish: ‘Fleet Street is to journalism – journalism as an act of civic responsibility, that is – as military music is to music. Fleet Street is in the audience business rather than the news business, or it is an open rivalry between both impulses.’

Michael Wolff, The Man Who Owns The News, Bodley Head, London, 2008, p. 72.

![]()

… each juicy crime can go a long way: the horror of what happened, the police investigation (with endless opportunities for armchair criticism and wild conjecture), background about suspects, maybe a long trial, sometimes an appeal and, in especially infamous cases, an anniversary reprise. Little wonder crime seems relentless.

Interestingly none of this was even considered by Lord Justice Leveson in Britain’s biggest investigation ever into the press. When he described the ‘recklessness in prioritising sensational stories’, it does not seem to have occurred to him that, if denuded of context, the cumulative effects of any stories can be against the public interest. This pressure towards populism is compounded by the fact that most journalists are generalists and are schooled in the humanities. They are often ignorant of, and impatient with, statistics or scientific caution and, for them, opinions are prone to trump facts. (Quote is from The Times, 30 November 2012, p. 10, reporting Lord Justice Leveson, An Inquiry into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press, The Stationery Office, 2012.)

![]()

For example, in 2007 I was asked by the BBC Today programme to explain the latest falls in crime. The package was carefully pre-scripted, checked (not least with a Fellow of the Royal Society and of the Royal Statistical Society and the Professor of Public Understanding of Risk at Cambridge University) and pre-recorded the night before the show. But after I went home a producer panicked. He thought it might prove controversial to say crime was declining – so in pursuit of BBC neutrality he phoned round to get a rebuttal. Given that no self-respecting statistician would oblige he found a leader writer on the Telegraph who opined that of course crime was getting worse because ‘people feel it is going up’. Subsequently newspapers piled in, with a sneering editorial in the Mail: ‘Perhaps [Nick Ross] would have us tell folk to leave their doors unbolted, cars unlocked and tell Grandmother she can walk home alone after dark.’

And the news pages found a Tory front-bench spokesman to buttress the newspaper’s own self-interested perspective: ‘We all know Nick Ross is meant to be a great national treasure but he’s doing exactly what Labour ministers do, he’s being very selective with his statistics.’

Today programme, Radio 4, 21 July 2007, 8.43am.

Mail on Sunday, 22 July 2007. [http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-470059/Nick-Ross-accusing-media-distorting-crime-figures.html]

[See also http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/greenslade+nick-ross.]

![]()

As Max Hastings, one of the most revered British journalists, observes: ‘Journalists often generate synthetic indignation. Indeed, the ability to do so is almost indispensable to media success.’

Max Hastings, The Observer, London, 18 March 2007, p. 43. This incincerity is not confined to crime reporting. For example, editors who adopt an outraged moral tone if celebrities or politicians have extramarital affairs are then shown to have committed adultery themselves, including those from the shrillest tabloids like the Sun and now defunct News of the World.

![]()