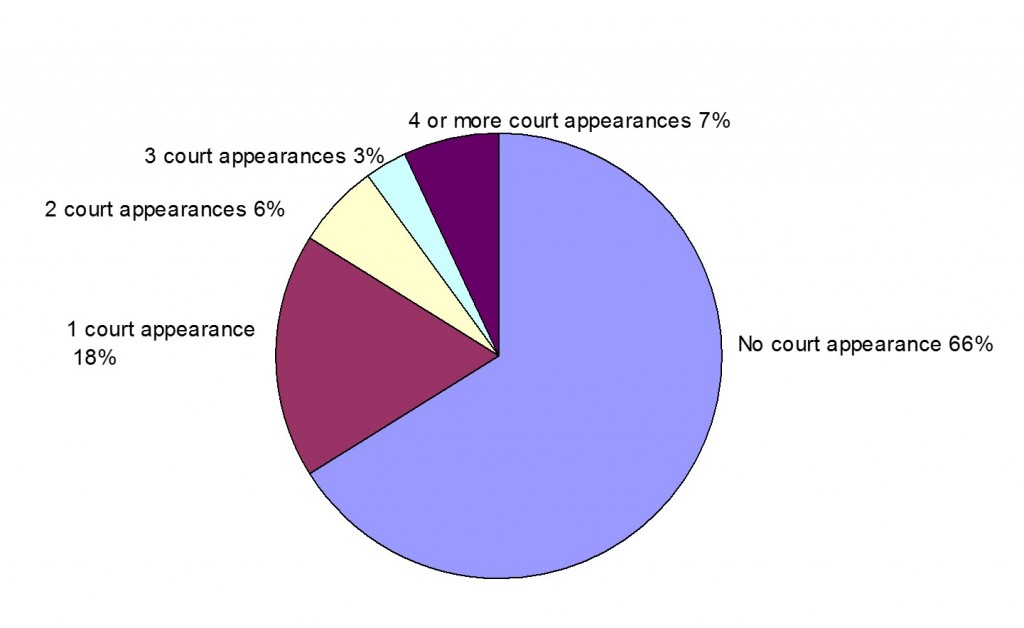

A third of British males born in the 1950s had acquired a criminal conviction by the time they were middle-aged.1 If you think that sounds fantastic, several follow-up studies have shown similar results.2 Taken at face value, that means it is more usual for a man to be sentenced for a crime than to be a smoker.3

1 J. Prime, S. White, S. Liriano and K. Patel, ‘Criminal careers of those born between 1953 and 1978’, Statistical Bulletin 4/01, 2001, Home Office. [The National Archives have a fuller list of research outcomes that echo these findings (Ref HO421/2) at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ERORecords/HO/421/2/P2/RDS/DIGEST4/CHAPTER3.PDF.]

2 Other studies of offending rates came up with similar findings. For example, the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development followed males in south-east London born between 1952 and 1954, and found 33 per cent had acquired a criminal conviction by the age of twenty-five. See David Farrington and Farrington Per Olof Wikström, ‘Criminal careers in London and Stockholm: A cross-national comparative study’, in E. G. M. Weitekamp and H.-J. Kerner (eds) Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behaviour, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1994.

3 The figures on smoking (26 per cent of males) are from the General Household Survey, Smoking and drinking among adults, 2004/05 [www.statistics.gov.uk/ghs].

Court appearances of males born in 1953 up to their 40th birthday (England & Wales)

![]()

Provided we can remain anonymous, most of us admit to criminal acts. This excludes most trivial and motoring offences and it includes quite a lot of violence.

John Graham and Benjamin Bowling, ‘Young people and crime’, Home Office Research Study No. 145, 1995. This research showed that a fifth of males admitted criminal acts while showing none of the risk factors traditionally associated with crime. One in four males confessed to offences of violence. [http://www.esds.ac.uk/doc/3814%5Cmrdoc%5Cpdf%5Ca3814uab.pdf]

![]()

Almost half the Britons would evade income tax, two-thirds would dodge a fare or install illegal software, almost as many would steal office stationery and over a quarter would filch a hotel towel.

Of the Britons surveyed, 46 per cent would evade income tax, 66 per cent would dodge a fare or pirate software, 60 per cent would steal from the office stationery, and 28 per cent would filch a hotel towel. Readers’ Digest along with many newspapers and academic studies has also experimented by dropping wallets complete with cash and identifying details, and secretly observing who picked them up. Usually about two-thirds are returned intact. Similar experiments have used letters left on the street.

![]()

In a separate study most people admitted to fraud and theft they had actually committed. Over three-quarters they had accepted too much change in a shop, a third had fiddled their expenses, and over a quarter had shoplifted.1 In another survey almost half of 14–21-year-olds questioned in the UK said they had committed a criminal offence within the last year. (Swiss and Dutch kids confessed to even more.)2

1An exploratory survey by V-W Mitchell and J. K. L. Chan, Investigating UK Consumers’ Unethical Attitudes and Behaviours, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 18, 2002, pp. 5–26.

2 Other European youngsters admitted to offending more in the previous twelve months (61 per cent in the Netherlands, and 72 per cent in Switzerland). Source: J. Junger-Tas, G-J Terlouw and M. W. Klien (eds), Delinquent Behaviour Among Young People in the Western World: First Results of the International Self-Report Delinquency Study Amsterdam/New York, Kugler, 1994.

![]()

Speed cameras were vilified and had to be painted yellow so that people could see them and slow down, and hundreds were scrapped in what one newspaper described as ‘a victory for motorists and fair play’.

[www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-115574/Hundreds-speed-cameras-scrapped.html#ixzz2DGye3ca0]

![]()

Even after 2011, when Britain’s roads were at their safest since records began in 1926, motoring still created three times more victims than homicide.

At one time there were as many drink-drive fatalities as there have been total fatalities in recent years. In 1979 1,640 deaths and 8,300 serious injuries were caused by drink-driving [http://www.drinkdriving.org/drink_driving_statistics_uk.php#accidentstatistics] compared to 546 homicides [http://www.murderuk.com/misc_crime_stats.html]. In 2011/12 there were 1,790 road fatalities [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-18881049] and 640 homicides (Home Office and Scottish government figures).

![]()

According to the Treasury, the basic rate of income tax could be cut by at least 2p if everyone ‘simply paid up what they owed’.

Danny Alexander, Britain’s Chief Secretary to the Treasury, speaking on BBC TV Sunday Politics, 22 July 2012. George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, called tax dodgers ‘morally repugnant’.

![]()

In 2012 a reporter for The Times, posing as a highly paid IT consultant, had no problem finding lawyers and accountants eager to hide his money from the Revenue. One genial tax-dodging expert promised to cut his tax bill from 45 per cent to 1 per cent. ‘We can’t explain on paper what we do,’ he said. ‘It’s a game of cat and mouse.’1 Among that firm’s 1,100 clients was the comedian Jimmy Carr, who sheltered over £3 million a year from tax and was able to rationalise his own amorality while ridiculing tax scams by others.2

1The Times, 19 June 2012, pp. 1, 6–8.

2 Carr’s satire on tax advisers included the line: ‘Why don’t you apply for the Barclays 1 per cent tax scam. You’ll need the world’s most aggressive team of blood-hungry amoral lawyers…’ Once his own role in avoidance became public he apologised for his failure of judgement, much to the ire of John Hughman in Investors Chronicle: ‘How is prudent financial management “a terrible mistake”?’ [http://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/2012/06/22/comment/chronic-investor-blog/out-of-cats-would-avoid-paying-tax-if-they-could-ChqR090c4npCzDVNBqkVZJ/article.html]

![]()

McKinsey and Company’s former chief economist reckons the world’s super-rich alone have squirrelled away £13 trillion, which is the size of the US and Japanese economies combined. That is straight cash deposited in tax havens and excludes undeclared assets like property, private jets and yachts.

The Price of Offshore Revisited was compiled in 2012 by McKinsey’s former chief economist, James Henry, who analysed holdings in private banks like UBS. The report was commissioned by the Tax Justice Network, which is a British political research and campaigning body backed by lawyers, accountants and aid charities. It assumes that the offshore sector ‘specialises in tax dodging’, but since some of the investors live or trade in relatively unstable countries they may have motives other than tax avoidance. [http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/The_Price_of_Offshore_Revisited_Presser_120722.pdf]

![]()

McKinsey and Company’s former chief economist reckons the world’s super-rich alone have squirrelled away £13 trillion, which is the size of the US and Japanese economies combined. That is straight cash deposited in tax havens and excludes undeclared assets like property, private jets and yachts.

The Price of Offshore Revisited was compiled in 2012 by McKinsey’s former chief economist, James Henry, who analysed holdings in private banks like UBS. The report was commissioned by the Tax Justice Network, which is a British political research and campaigning body backed by lawyers, accountants and aid charities. It assumes that the offshore sector ‘specialises in tax dodging’, but since some of the investors live or trade in relatively unstable countries they may have motives other than tax avoidance. [http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/The_Price_of_Offshore_Revisited_Presser_120722.pdf]

![]()

Michael Snyder, chairman of the City of London’s policy committee, describes the huge temptations for fraud in the financial capital as ‘a billion-dollar problem rooted in a trillion dollar success’.

Michael Snyder, chairman of the City of London’s policy and resources committee, Financial Times, London, 31 July 2006, p. 15.

![]()

A report from the Chartered Institute of Building, the trade body of the construction industry, found that 75 per cent of British construction professionals thought bribery to obtain a contract was not corrupt, and that falsifying accounts or invoices is acceptable and commonplace.1 Such dishonesty has been tacitly backed by governments, not least with the UK’s ‘biggest sale of anything to anyone’, the Al Yamamah contract to supply Saudi Arabia with sophisticated weapons.2

1How Corrupt is the Construction Industry, Chartered Institute of Building, Berkshire UK, October 2006 [www.ciob.org.uk].

2 Bribery allegations swirled around the Al Yamamah contract since its inception in the early 1980s, and it is widely suspected that consultancy payments were routine in earlier arms sales too. But the Al Yamamah deal was so colossal and so sensitive that the scandal threatened to envelop the government and Margaret Thatcher’s son, as well as the prime contractor, BAE Systems. It is the only case where Britain’s National Audit Office concealed the result of one of its inquiries, and spectacularly in December 2006, under pressure from the Saudi government, the Attorney General directed the SFO to discontinue its investigation, prompting dismay among OECD partners who suspected Britain was covering up large-scale unfair trading. BAE Systems was also investigated for bribes elsewhere, including South Africa.

![]()

Great institutions like Citicorp and Credit Suisse First Boston pretended to give unbiased advice while being up to their necks in deals they recommended and, like Goldman Sachs, ‘ripping their clients off’ and deriding them as ‘muppets’.1 British banks rigged inter-bank lending rates2 and ‘mis-sold’ pensions. Other major firms swindled their investors.3 Huge corporations like WorldCom were out-and-out frauds. Many other great names tumbled because of criminal conspiracies, including Enron, Entersys and ImClone and Tyco.4 One of the world’s biggest auditors, Andersen, was found to have conspired to cheat the very shareholders it was paid to protect, and one of the biggest banks, HSBC, helped launder billions of dollars on behalf of drug cartels, rogue regimes such as North Korea, and even al Qaeda.5

1Greg Smith resigned as an executive director of Goldman Sachs, denouncing the bank in a New York Times editorial as ‘toxic and destructive’. ‘It makes me ill how callously people talk about ripping their clients off. Over the last twelve months I have seen five different managing directors refer to their own clients as “muppets”, sometimes over internal email.’ [http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/opinion/why-i-am-leaving-goldman-sachs.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0]

2 In 2012 Barclays was fined £290 million for trying to manipulate Libor in what the Chancellor of the Exchequer described as a ‘shocking indictment’ of British banks. Traders in the bank were getting colleagues to distort the figures so they could bet against the wholesale money. They even manipulated rates for friends in other banks. Barclays chief executive, Bob Diamond, who resigned in the wake of the scandal, called it despicable and reprehensible: it made him ‘physically ill’ (Evidence to Treasury Select Committee, 4 July 2012). More than £3 billion was wiped off Barclays’s value. It turned out that other banks were running similar scams and RBS was fined heftily by the regulator.

3 For example the biotech company Bioglan was caught ‘round tripping’ revenues, churning money to inflate its worth and many other firms have indulged in controversial accounting practices including AOL, Global Crossing, Qwest Communications and Sun Microsystems.

4 WorldCom was the US telecommunications giant caught out in 2002 in an $11 billion fraudulent accounting scandal. Enron had been America’s seventh-largest firm, reporting mounting profits but hiding $30 billion in debt before its implosion in 2001, costing 20,000 jobs and wiping out $2 billion in pensions. Executives stole millions and bribed tax officials and, according to the chairman of the US Senate Finance Committee inquiry, ‘The report reads like a conspiracy novel, with some of the nation’s finest banks, accounting firms and attorneys working together to prop up the biggest corporate farce of this century.’ ImClone was a biotech firm involved in insider trading, fraud, perjury, obstruction of justice and conspiracy which, among other people, implicated America’s favourite home decorator and TV star Martha Stewart. Tyco was a blue-chip firm, some of whose executives siphoned off huge sums of money.

5 US Senate hearings, 17 July 2012. The scandal led to the resignation of David Bagley, HSBC’s compliance chief.

![]()

… for every headline-grabbing conman like Robert Maxwell or Conrad Black, Nick Leeson2 or Bernard Madoff,3 much (and maybe most) skulduggery is never detected at all.

1At least two newspaper magnates were crooks. Robert Maxwell, owner of the Daily Mirror, plundered the pensions of his staff, and Conrad Black, owner of the Daily Telegraph and The Spectator, was shown to have milked his shareholders on both sides of the Atlantic. The biographer Tom Bower helped expose both of them. See Maxwell: The Final Verdict, 1995, and Conrad & Lady Black: Dancing on the Edge, 2006, Harper Collins.

2 Nick Leeson bankrupted Barings, one of the world’s oldest and most prestigious banks, and his exposure was followed by a string of similar cases including Jérôme Kerviel, who cost Société Générale €5 billion, and Kweku Adoboli, who lost £1.4 billion of UBS’s money. The banking sector is an obvious place to seek opportunities for crime. It deals in lots of money and its so-called casino operations take place in a cloistered world which is often poorly regulated and impenetrable to other financial specialists. Imagine yourself out of the public gaze and presented with huge enticements. Unsurprisingly, many traders found it irresistible.

3 Charles Ponzi lent his name to the English language in the 1920s, persuading people he could deliver 40 per cent annual returns which he paid not from profits but by passing on 40 per cent of new investments and keeping the rest for himself. Bernard Madoff got away for years with a similar pyramid scheme until the stock market crash of 2008 caused investors to want their money back. Wealthy individuals and shamefaced institutions, including some of the world’s biggest banks, admitted they stood to lose $20 billion while Mr Madoff himself reckoned he had conned them out of $50 billion. It had been in no one’s interest to see that the Midas emperor had been riding through Wall Street naked. And Madoff was just a conspicuous example of people’s lack of foresight when profit – especially implausible – profit is to be made. It is what led to surges and crashes through stock market history from the tulip mania of 1637, through the South Sea Bubble of 1720 and the railway share disaster of 1845, the dotcom crash of 2001 and to many smaller ruinations like the Bitcoin fiasco of 2013.

Yet some of it is titanic, especially in the public sector, where chains of ghost transactions called carousel frauds cost the Exchequer a fortune

European carousel frauds involve importing high-value goods like computer chips from another EU country free of VAT (sales tax), then selling them on plus VAT but disappearing without handing the tax on to the government. There are many variants, such as re-exporting and importing, or milking VAT through whole chains of missing traders, or simply issuing false documents to claim back VAT.

![]()

Yet some of it is titanic, especially in the public sector, where chains of ghost transactions called carousel frauds cost the Exchequer a fortune

European carousel frauds involve importing high-value goods like computer chips from another EU country free of VAT (sales tax), then selling them on plus VAT but disappearing without handing the tax on to the government. There are many variants, such as re-exporting and importing, or milking VAT through whole chains of missing traders, or simply issuing false documents to claim back VAT.

![]()

The accounting firm BDO Stoy Hayward conducted an annual survey which suggests only 15 per cent of businesses report their losses to the police.

BDO Stoy Hayward have run annual surveys of fraud in the UK and internationally, and estimate fraud in Britain cost businesses £2 billion in 2011.

![]()

Not much has changed since, two-and-a-half centuries ago, Adam Smith, the father of economics, noted that self-interest is the engine of industry: ‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.’

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776, Ch. 2

![]()

In 2008 an audit in the British Army found soldiers were treating expenses as a ‘cash machine’. According to the chief of staff, dishonesty was so widespread that ‘every single sample they have looked at this year has turned up examples of fraud’.

Lt-Gen Sir David Richards, chief of staff, expressing his concern at ‘the prevalence of fraudulent behaviour’ among troops, quoted in the Sunday Times, London, 23 November 2008.

![]()

… the endemic nature of the problem can be judged from the fact that the Olympic Games involve thousands of random blood and urine samples and require dope-tests on all top five athletes in every competition.

Nor was it just the competitors. The Olympic movement was transformed from an amateur sports fixture into a commercial empire awash with billions of dollars and, with few checks and balances, corruption naturally became endemic. IOC officials lived and travelled in luxury, ‘routinely’ took bribes and siphoned off large amounts of cash (ref: Matthew Sayed, The Times, 22 April 2010, p. 23).

![]()

… the code of silence is as strong in the professions as it is in the criminal underworld. Telling tales is discouraged and whistleblowing needs almost reckless courage.

Whistleblowers rarely have an easy time of it, disparaged for ‘ratting’ or at very least being ‘not team players’. Sadly, and appallingly, this is even true in the medical profession, where patients’ lives are at stake and, indeed, are sometimes forfeited because of the ‘professional’ code of silence. Not just negligent doctors but crooked ones too have been shielded by colleagues who failed to warn the authorities. Doctors whom I regard as saints in other ways have told me quite openly that they would keep quiet even if they knew a fellow clinician was dangerous. Confronting this long-standing immorality should be a priority for medical schools and all other medical institutions.

The pharmaceutical industry is a conspiracy in its own right. It has indulged in so much shenanigans that leading evidence-based doctors and scientists have compiled whole books documenting widespread deceit and fraud. According to Peter Rost, the former marketing manager of Pfizer, who was sacked for unmasking a cartel, “It is scary how many similarities there are between this industry and the mob. The mob makes obscene amounts of money, as does this industry. The mob bribes politicians and others, and so does the drug industry. The side effects of organized crime are killings and deaths, and the side effects are the same in this industry.” Rost’s analogy may not be an overstatement given that the adverse effects of pharmaceuticals cause more deaths than anything but cancer and heart disease. For more on the breathtaking extent of ethical lapses see Peter Gøtzsche, Deadly Medicines and Organised Crime, Radcliffe Publishing, 2013; and Ben Goldacre, Bad Pharma, Fourth Estate, 2013; or see http://www.dcscience.net/?p=6567.

![]()

What we do know is that the law had to be changed to protect clients from investment advisers;1 that ambulance-chasing lawyers are a menace and that each year dozens of solicitors are struck off or entire firms are censured for bending the rules;2 that university dons have been caught on camera cheating on marks to improve the college pass rate; and that estate agents have rigged markets, gone for fast commission rather than best price, removed rival sale boards, and even on occasions supplied fake documents.3 And we all know the venality of the bonus culture. As the veteran City commentator Neil Collins observed, ‘Performance rewards are manipulated to get the number you first thought of.’4

1Britain’s Financial Services Authority introduced the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) in 2013 to ban commission payments after concluding they could be seen as an inducement to distort guidance advisers were giving to their clients.

2 Lawyers usually do best working within the rules; even so about one in fifty will be disciplined or struck off in the course of a career. As with other white-collar groups, the professions bodies purport to represent the public but are really trades unions. An illustration of their role was a spat over state subsidies to lawyers in England and Wales. Legal aid costs well over £2 billion p.a. and is supposed to be paid back if clients win damages. But many legal firms just kept the money, and when in 2006 attempts were made to recover the cash, the Law Society of England and Wales expressed outrage; just as criminals rationalise theft by blaming their victims, it blamed the authorities for their ‘failure to collect money in a timely way’.

3 No doubt there are many honest professionals, just as there are many honest blue-collar workers and unemployed, but there have been many exposures of corrupt and unethical estate agency practices. According to the Office of Fair Trading, unfair and unethical treatment within the industry is prominent. It is also well known. A TV programme, Whistleblowers (BBC One, 21 March 2006), had two reporters working undercover and exposed a catalogue of cheating, including an agent providing a fake passport to help secure a mortgage.

4 Financial Times, 30 June 2012, p. 18.

![]()

The Canadian criminologist Thomas Gabor may exaggerate a little in the title of his book Everybody Does It, but he is spot on that:

Dividing all of humanity into two camps – the decent and the villainous – is at odds with the facts … almost everybody violates criminal or other laws on occasion. Crime … is more like the common cold – an affliction to which no one is completely immune but to which everyone is not equally susceptible. This all-or-nothing dichotomy is an antiquated view.

Thomas Gabor, Everybody Does It: Crime by the Public, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Buffalo, London, 1994.

![]()

Around half of young people surveyed are relaxed about stealing software or music and don’t believe it should be punished.

A report in 2013 commissioned by NBC Universal found more than a quarter of Internet users explicitly sought out copyright infringement, such as pirate films or software. Other examples of research into attitudes to online piracy include: Oleksandr Gruk, Detailed analysis of methods and attitudes of illegal music downloading and copyright infringement, Metropolia Univ, Helsinki, 2011. [http://publications.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/39222/Oleksandr%20Gruk_Bachelors%20Thesis.pdf?sequence=1] and an online survey conducted by KRC Research on behalf of Microsoft in 2008 [http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/news/press/2008/feb08/02-13msipsurveyresultspr.aspx].

![]()

And along with the phony Viagra, gold watches that rust and DVDs recorded from the back row of a cinema, there are sub-standard baby powders, cigarettes high in arsenic,1 antibiotics and contraceptive pills with no active ingredients,2 unsafe car parts and even forged aircraft components.3

1In 2013 a European survey for the tobacco industry checked thousands of discarded cigarette packs and concluded that more than a quarter of cigarettes smoked in the UK were counterfeit. The Times, 4 March 2013, quoting a report by Geneva-based MSIntelligence. [www.msintelligence.com/services_overview.asp].

2 The WHO reports that 30 per cent of drugs used in Africa and south-east Asia are fake (source: PA Consulting Group). It is an ‘epidemic of killer medications’ according to The Guardian (24 December 2012) and many medicines, including malaria pills, have no active ingredient.

3 The enormous scale of bogus aircraft parts emerged after a Norwegian airliner (Partnair Flight 394) broke up in flight in 1989 killing all 55 on board. Investigators found that bolts holding the tail in place were counterfeit and had snapped. It soon transpired there was a huge black market in aircraft parts, so much so that when the US Federal Aviation Authority checked its own inventory it found a third of its stock was illegal. Fake parts had even been fitted to Air Force One. An inquiry revealed there were 5,000 aircraft brokers in the US alone, sourcing components from from scrapyards or bogus manufacturers and frequently supplying them with forged FAA certification tags. Despite new regulations, Britain’s air crash investigators say fake parts are still recovered from crashed planes (AAIB chief in conversation with the author).

![]()

… it turns out MPs are rather like the rest of us. In 2008, details began to emerge that several of them had abused allowances.

Ministers plainly knew about the scandal and tried to hush it up, with Harriet Harman, Leader of the Commons, tabling a motion specifically to exempt MPs’ expenses from Freedom of Information requests. In addition, House of Commons officials lost two legal cases hoping to keep claims secret, and even then failed to publish them as instructed by the High Court.

![]()

… given the politically explosive nature of the story, someone thought to steal a complete list of parliamentary expense claims and tout it to national newspapers for £150,000. Since it was plainly stolen property, at least two editors turned it down

1One of the many ironies of this story is that The Times and The Sun, both papers in the Murdoch stable which was soon to be vilified for lack of ethics, turned the thief away.

![]()

An anonymous survey of MPs a decade earlier found that a sizeable minority conceded they would cheat if no one asked them to pay for a bottle of wine or a train fare.

Anonymous survey of MPs, Evening Standard, 29 December 1998. Curiously, Conservatives claimed to be most scrupulous, Liberal Democrats least so; but perhaps that is because the Lib Dems were more honest in the questionnaire.

![]()

In any case, Parliament has long hosted scandals, with peerages and other honours being sold for party favours, fiddled expenses, illegal donations and backhanders such as ‘cash for questions’. Sleaze helped sweep the Conservatives from power in 19971 and came to dog Labour just as badly.2

1Several MPs were paid to represent vested interests and ask ‘helpful’ questions in the Commons, leading to the disgrace of a former minister, Neil Hamilton. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, the Conservatives became synonymous with sleaze. Among the more notorious scandals, the former leader of Westminster council was ordered to pay £27 million for gerrymandering by selling council homes in marginal wards, and a minister (Jonathan Aitken) and deputy party chairman (Jeffrey Archer) were jailed for perjury.

2 Under Labour there were substantial and persistent illegal donations to the party and failures to disclose financial dealings or favours such as subsidised homes and holidays. There were ‘cash for access’ scandals amid claims that big party donors like Bernie Ecclestone got special treatment, followed by several criminal investigations involving senior figures. A cabinet minister, Tessa Jowell, survived questionable financial dealings by her husband, and two cabinet ministers, Peter Mandelson and David Blunkett, each resigned twice amid accusations of favouritism and financial irregularities.

![]()

Interestingly, the Tory grandee Lord Tebbit, known as the Chingford Skinhead and a ‘semi-house-trained pole cat’ for his uncompromisingly tough views, showed great understanding when it came to fellow politicians: ‘Members of the House of Commons are neither subhuman nor superhuman. They are as prone as the rest of us to give in to temptation.’

Daily Mail, 4 February 2008, p. 9.

![]()

We even cheat when we have little need to. The psychologist-cum-economist Dan Ariely tested this on privileged students at Ivy League universities …

The second, and more counterintuitive result, was even more impressive: once tempted to cheat the participants didn’t seem to be as influenced by the risk of being caught as one might think.

Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, HarperCollins, London, 2008, p. 201. See also Ariely’s The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, HarperCollins, 2012.

![]()

‘None of this makes sense,’ he wrote, ‘but when the medium of exchange is nonmonetary, our ability to rationalize increases by leaps and bounds.’

Ibid. p. 224.

![]()

Yet, in its own way, Middle England seems perfectly capable of cutting corners, and the rich and even super-rich are not exempt.

All the biggest frauds and insider trades are conducted by those who have the opportunity and thus proximity to money. Yet few of them need the cash. Like Ariely’s students, they cheat because they can, including legendary figures like Rajat Gupta who, as head of the consultancy McKinsey, was one of the most trusted and best-connected figures in the corporate world.

![]()